|

The Cal 28 Sailboat from Jensen Marine |

|||

|

|

These are the adventures of "Gangfurd," a 1965 Bill Lapworth designed Cal 28. Formerly, "Pirate," we bought her on eBay in January 2006. Prior to that time our sailing experience was limited to sailing a gaff-rigged Sharpie [looked like a Lightning - about 19'] on the Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and racing a Mobjack [about 21'] on the Chesapeake Bay and the Potomac River. We crewed with a guy named David Berger, and we won the 1967 Mobjack Class Championship for the District of Columbia. There were the occasional Hobie Cat and Catalina 22 rentals on Mission Bay, as well as a few Catalina 25 rentals off the Hotel del Coronado in San Diego Bay. Those days were long ago when we were very young. Recognizing time was growing short, and it was now or never, we seized the moment. With a mere five minutes remaining on the eBay auction, we dove in. We emerged victorious and somewhat in shock at what we had done. The auction fine print said we had a mere two days to take possession of the boat and move her out of the guest slip at Oceanside Harbor in North County San Diego. Maybe that last frenzied click of the mouse was ill-advised. A drive to Oceanside and a meeting with the

fine people at Oceanside Harbor proved fruitful, if not expensive.

Our first grandchild's future secured, we were extended another twenty

days, surely time enough to locate a new slip in another city and/or

buy a sailboat trailer large enough to haul a 28 foot 6,000 pound

sailboat to Mexico. Not.

But hey, why worry? We opted for a shake down cruise in the Pacific. We spent the first day hanging out on the boat and contemplating what we had done. Did I mention the fog the day we arrived? Pea soup. We bought a fog horn, just in case. We checked her over from bow to stern, hauled out the sails, played with the radio, tested the microwave, bought a heater, bought some sleeping bags, bought new lines for the large Genoa, and generally began to experience the reality of our predicament. As best we could determine, and according to the hull survey mentioned in the eBay ad, she checked out just fine. A few fuses later and the electrical system appeared in order. A single pull on the Nissan 9.8 outboard fired her right up. Water continued to pass through the engine and no steam developed, and she sounded great. A bilge check revealed nothing but condensation. The bilge pump worked. We ran the main sail and Genoa up at the dock to familiarize ourselves with the rigging. Then, with the sails still up, we elected to motor sail out of the harbor and into the Pacific. Lacking any real control in reverse due to the raised sails, we backed out of the slip and stalled the engine trying to shift into forward gear. A sense of emerging panic evaporated quickly as the Japanese engineered Nissan fired up again on the first try. Our sideways drift just off the guest slip ceased and we were propelled forward under power. We headed towards the harbor mouth, where we heard from the locals that at times large swells terrorized boaters. Tales of returning sailboats surfing through and around the rock jetty got our attention. We made it through without incident, but we took care to observe the surrounding rocks. On the radio that morning we learned of another 28 foot sailboat that was smashed by a whale the previous day. What precipitated that? Wary of rocks, swells, and whales, we headed for blue water. We sailed for a couple of hours and were impressed by how she handled easily. We returned to Oceanside without incident and tied her down for the night. Then we left California. Several trailer auctions later, we again ventured back to Oceanside. Still no trailer. Our other crew member, my brother, had worse things to do, so he could not return with us. We were surprised to learn that the lines were fouled. We discovered this at sea trying to raise the sails. Completely unable to unfoul them in the rolling and pounding sea, we returned to port with the incoming tide. It proved a challenging event with the tide, current, and wind working against us. We abandoned our first approach and pulled out again, made a quick turn around and again approached the dock. On only our second docking attempt since buying the boat, my crew tied off the bow line quickly. By the time I left with the stern line, the tide, wind, and current carried the stern away from the dock and she was swinging completely around. Earlier, the sailboat owners next to us suggested we back her in the next time to allow us to work on the algae growth on the motor. No one could raise the engine out of the water. Watching the 360 in progress, we did our best to make it look like an intended maneuver. Our deception was revealed when the Nissan 9.8 outboard came into contact with the dock on the far side of the slip. I though I'd managed to wedge the boat across the slip. Fortunately, she swung all the way around. We tied her in place and began clearing the fouled lines. No harm was done to the outboard. Next, we hoisted all sails while still at the marina. All functioned properly. After ten minutes, we raised the sails and headed out into the Pacific. We sailed west, straight away from the coast line in the direction of a regatta of Shrock 22's. We headed for the committee boat to try to catch the last leg of the race. Closer to land than the racing 22's, it was obvious their distance from the coast favored them with stronger winds. They bore down on us as we remained becalmed and bobbing in the seas, wind spilling from our sail with every passing swell. Sailing with a crew member who had only been in a sailboat a total of five times, we jibed directly in front of the committee boat as we tried to come about. Not cool. It was my fault, and not my crew member's. I explained to my crew just how bad our jibe looked to those on the committee boat. On the same tack now as the racers, were able to charge after them on the port tack, blasting towards the harbor entrance. My now more experienced crew made landfall with an incoming tide, wind, and current. The crew of the lobster boat watched with interest and stood by to lend aid as we approached the slip. My crew hesitated when ordered to drop on to the dock. I dropped from the cockpit and secured the stern line. We looked like we had done this many times. The lobster captain commented that we looked good, and that we should have seen his entry just minutes before. "It got pretty gnarly." Another successful outing and we left town again. Convinced we could never successfully navigate and sail from Oceanside to San Diego's Chula Vista Marina in one day, I sought additional crew. Fortunately, my brother was just as excited about Gangfurd as I was. He offered to fly into San Diego to assist in our effort to make it to the new slip in San Diego's far south bay. The day arrived and we all descended on San Diego and Oceanside from Phoenix. Myself by car, while the others flew into town. Debbie flew in first and spent the night aboard at the Oceanside Marina, where she had a wonderful day. She described it as "the best day of my life." Hmmmm . . . . Friday morning the sun was up and a beautiful day awaited us. According to all weather reports, we were supposed to have beautiful weather until Sunday. We bought additional life jackets, a ladder, and some other last minute provisions, and watched as diver Joe came and scraped the bottom just before we left. Joe checked out the bottom and pronounced the bottom paint messed up from a red tide, but that otherwise she was in great shape. We gassed up and made for blue water. Main sail and Genoa flying bright in the morning sun, Captain Debbie took us straight west away from Oceanside. The plan was to sail about five miles off the shore and then south to San Diego. Others reported that even motor sailing, the trip to San Diego would take about eleven hours. Winds were from the north, as was the current. The conditions were right for a great trip. Only a few other boats were out on the water, which surprised us. We rapidly reeled in any in front of us and kept heading west. We were the only boat in sight headed to San Diego. We continued a westerly course until the wind died. Realizing time was running short due to our late departure, we knew we'd never make it on time under sail. We planned to break the trip into two days, the first to Mission Bay, followed by our triumphant entrance into Chula Vista Marina. It was already late afternoon and we were close to becalmed on the water. The decision was quickly made to "fire that Nissan up." We knew we were now dependent, like the true sailors we were, on our small outboard. The Nissan 9.8 two stroke fired right up and we put the pedal to the metal. The combination of the sails and motor gave us a whopping 7.8 mph. The sun was dropping over the Pacific, and we knew it would be close getting to Mission Bay before nightfall. Our new Garmin GPS projected a night landing, but we hoped to make land before dark. We motor sailed on without incident, completely alone on the ocean, except for the gulls and pelicans. No other boats were in sight, except for a single large fishing trawler when we neared San Diego. We successfully avoided the La Jolla Kelp Bed on our first trip.

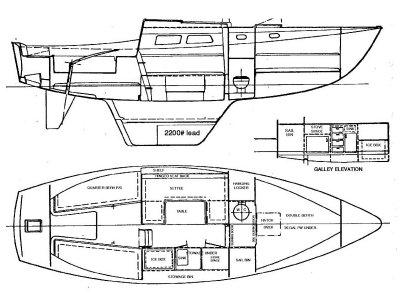

With the sun dropping in a colorful salute to our arrival into Mission Bay's channel, we high-fived ourselves on a victorious landing before dark. We captured the sunset and our arrival on video. We turned on our night cruising lights and proceeded into the channel. Now we just needed to find a place to stay. We were told about Mariner's Cove, and we heard there were guest slips available elsewhere in the marinas. Without a tender, we elected not to enter Mariner's Cove, where we could see many other boats at anchor. We knew of the Dana Inn from previous trips, and we knew of the Dana Landing, which we thought would be the perfect place to spend the night. We headed for the first bridge traversing the bay. The wind really picked up as we entered the bay, and we gained considerable speed. As we neared the middle and highest bridge span, we noted the tide depth and the height markers on the concrete pillars supporting the bridge on West Mission Bay Drive. The painted notice said masts over 38 feet would not make it under the bridge. At this point we realized we did not know the precise height of our mast, but eyeballing it in the rapidly failing light, we looked good to make it, no problem. We maintained our course directly beneath the highest span. I sailed smaller rented Catalinas under this same bridge many times without worry, and the sailboat rental people said we could sail under this bridge. They did warn me not to go under the Ingraham Street bridge further inside the bay. Suddenly, with a mere four feet remaining to the bridge, it became very clear our mast was too tall and we were going to hit the bridge. My adrenaline kicked in, and we came about in record time. The boat responded perfectly, spinning on a dime and away from what surely would have been our first dismasting! The sun had just dropped below the horizon. Our earlier celebration was premature. Amazed we were not now dismasted under the bridge radioing for help, and still unable to believe how close to a complete disaster we just experienced, we headed into the area of the bay where we'd rented Catalinas in years past. We wondered how we could have come this far without knowing the dimensions of our craft. We knew her length, beam, and draft, but we never considered the mast height for our open ocean sail. I knew we would make it below the Coronado Bridge. We just never thought about the bridges of Mission Bay. I blamed myself, and the lack of Cal 28 information on the Internet. I remembered now the poor quality scan I captured online. It dawned on me I never really could read the dimensions stated on the diagram. Note to self: measure that puppy before ever going near another bridge. Note to others buying used boats on eBay: get all of the original documentation you can. My bad. We cruised all available mooring sites at the marina and came up empty. The sun was now gone and we continued our search in darkness. We recognized the marina where we'd rented Catalina's in days gone by off of Quivira Road and saw the only available slip. We tied up at the dock behind a Catalina and headed to the office, which now appeared closed. We found an employee still securing rental motor boats and explained our predicament. He said he knew of no available guest slips anywhere in the area and simply stated we could not tie up for the night at that location. Thanks for nothing. Note to self: do not rent any boat from that place again. We cast off into the darkness wondering what good fortune awaited us next. We made the rounds of the marina and found no empty slip. At this time, we voted to continue on around Point Loma and into San Diego Bay. We earlier dropped the sails following our close encounter with the bridge, so we elected to power all the way to San Diego. We would evaluate later whether to proceed in the night to the Chula Vista Marina in the south bay. Cursing the boat rental guy, we headed west back out the Mission Bay channel into the open Pacific. The sun was gone now. We were now on our first night cruise in open water, like it or not. The Pacific Ocean looking west was pitch black. The view to the east showed the San Diego skyline reflecting off the water separating us and safety. The tide was still coming in as we headed into the black night, bow due west, up and over the incoming rollers, which appeared to be growing in size. The decision made, we motored into the black hole before us. We were dependent now on a Nissan 9.8 two-stroke engine to get us back. Keeping one hand firmly on the lifeline, and the other on the tiller, we plowed on. Fear of the unknown on my first night cruise made me relate to ancient mariners on the sea. An understanding crept forth about why sailors were so superstitious, and why they believed the world was flat. I knew somewhere out there existed a drop-off, or a sea monster, ready to pull me over and down into the deep water. I could relate to those who went before me on the oceans. The steady sound of the Nissan was reassuring, and every change in sounds was cause for concern. The only other sound was that of the halyards from the main sail and the genoa that we forgot to tie off. They clanged against the aluminum mast with each rise and fall of the oncoming rollers emerging from the dark. We bought a GPS, a Garmin GPSMap 76CS. While we knew computers, how to build them, and how to make web sites, we were still figuring out what the Garmin could do. We knew enough to buy and examine charts of the San Diego sailing area, and we knew there were at least two kelp fields we needed to avoid. On the way down, we made it around the La Jolla kelp without any difficulty. We followed our way points to Mission Bay without any problems. Now, heading out to sea, we knew there was one more kelp field to avoid. My brother and I continued into the night in this fashion for about 20 minutes. Every few minutes I asked him if he thought we were far enough out to avoid the kelp. Each time he looked back at the land, looked at the GPS, and say, "yeah, we're at least a mile out. We should be fine." Meanwhile, Debbie remained below decks. The three dramamine (sp?) pills she took for sea sickness knocked her out. The boat tossed side to side and up and down over the rollers. I wondered how Debbie was doing, but she was locked tight inside the cabin. The motor droaned on as we marveled that we were out on the Pacific Ocean at NIGHT! Never in our wildest dreams did we contemplate such a scenario. A mere 30 days earlier we were both just living our daily routines as lawyers in the desert, never suspecting one of us would be crazy enough to buy a sailboat on Ebay, or much less, that both of us were crazy enough to take her out on the ocean at night. I just asked my brother for the fourth time if he thought we would miss the kelp when it happened. The outboard sputtered, and then died. We both knew what happened. We were in the kelp beds. Forward progress stopped, as the boat tossed from side to side, still going up and over the incoming rollers. A quick look to shore showed the lights off Point Loma closer than expected. The scary blackness of the night caused me to hug the shore closer than planned. Now we had no motor power, and our sails were down. My brother jumped to the mast after we decided to hoist all sails. My brother stood at the mast, while he attempted to raise the main sail. Standing fully erect, he pulled on the halyard, but nothing budged. He barely maintained his balance on the tossing and rolling deck. I worried he was going to fall overboard. Neither of us was tethered to the boat. Dumb. It dawned on me then how dark the sea was, and how, if he did go over, I would never see him in the darkness. With that realization in mind, I went forward and sat on the deck by the mast and placed my arms around the mast and one of his legs, just to make sure. Debbie popped out of the cabin and asked, "what's going on?" We told her we got stuck in the kelp. She said, "oh," and returned below deck. Other than the kelp, going overboard, the problems with the halyards, and generally recognizing the problems we faced, I was worried about being pushed onto the rocks off Point Loma. The rollers were still coming in, and they were getting larger. I knew we had about a mile of sea room, but the words of every Patrick O'Brian and Hornblower novel came racing back to me. "They were caught on a lee shore!" At least, I thought we were, and that, according to Captains Aubrey and Hornblower, was a very bad thing. My brother continued hauling on the halyards without success. They were hopelessly tangled in the dark. He finally said, "check the propeller and see if you can unfoul it." Doubtful, I pulled a small LED flashlight from my pocket and headed to the stern of the boat. As I neared the transom, it occurred to me that it was always at this dark and anxious moment that the shark lept from the water, pulling its victim down to a bloody death. I very cautiously peered over the sternrail, shining my light into the black water, looking for any sign of a living creature. Seeing nothing, I poked my head out a bit further, ready to jump back into the cockpit at a moment's notice. Still no creatures. My light finally shone on the white propeller in the water, which was clearly visible now several feet below my reach and under the water. I wasn't going near it. No way. Then it dawned on me, I could see the white propeller! There was nothing on it! It must have snagged on the kelp, which then was worked free by the rolling and tossing of the waves. Eureka! I called to my brother and cautiously leaned over the rail and hauled on the starter rope. The Nissan fired right up! We were going to be all right. Our faith renewed, we plowed on further west, the end of the world be damned! I was going to make very sure that we avoided all other kelp near Point Loma. We roared on, slamming into oncoming rollers, and listening to the tangled rigging clanging in the night. Life was good. Twenty minutes later, we were again facing new issues for the first time. The motor sputtered again. We were running out of gas, and we were still not around Point Loma. We were still headed west to avoid the kelp. Renewed thoughts of the lee shore leapt back into my mind. Luckily, there were three gas tanks, and we filled all three just before leaving Oceanside. The trick was switching tanks in the dark Pacific night. Another first! Boat gas tanks are highly evolved. Fortunately, the tank designers must have faced this issue in a courtroom before, because the design of the mechanism was perfect. Like a Snap-On Tool, the gas line unplugged from the tank and plugged into the next tank just as nicely as you please. One or two pumps on the gas line and it was primed and ready to start. It started on the first pull. We motored on, really impressed now with Ebay and the design of the tanks. The night was cold. It was March on the Pacific, a place none of us had been before. We came prepared for wind, not cold. Our new sailing gloves left a lot to be desired in the cold and wet night. The tips of the fingers were cut from the index finger and thumb. Dew formed on every surface, including upon us. The resulting cold was kicking our butts. Sweat shirts, wind breakers, jeans, and tennis shoes were definitely not making it. We powered on and finally reached the mouth of the San Diego Bay in the wee hours of the morning. It was after midnight when we made our first approach into the bay. I remembered the warnings pronounced by other sailors before we left Oceanside, "it gets a little interesting off of Point Loma and coming into the bay." Why did I not ask exactly what he meant at the time? I was in the process of finding out now, first hand. As we entered what we thought was the main channel, we followed the green and red lights into the night. All was progressing just fine. We knew there were restricted areas marked all over our charts, so we kept a look out, not wanting to give some trigger-happy fool the right to blow us out of the water. Coronado stretched off to the south, and the lights of Tijuana shown brightly in the distance. We were in what appeared to be a very narrow channel very close to the Point Loma shore. I could not imagine a large aircraft carrier entering the same channel we were in, so I commented that we must be off course. My brother consulted the GPS, my wife surveyed with her eyes, and I could not bring myself to believe we were properly inside any channel large enough for submarines and aircraft carriers. A bouy sounded the presence of rocks to the south of us. I could see a rock wall emerging from the water, a feature never noticed in the three years I lived in San Diego. Where the hell did the rocks come from? On the other side of the rocks Coronado loomed large, a wide expanse of water reflecting the lights of that city. I was convinced we were supposed to be on the south side of the rock wall. The amount of water to the south was obviously wide enough to handle any carrier. My crew continued to doubt my assertions, citing the GPS system, the channel lights, and the rocks. We continued into the bay, moving slowly along the rock wall, and looking at earily lit fishing boats sitting on the water, aware of our passing as we slowly glided by. Not a word of caution or warning came from any of them, as we headed deeper into what everyone else thought was the bay. As we neared two cement pilings extending from the water into the air, warning signs visible, I feared I was going to run aground or, worse, be locked up for invading restricted waters. Just before gliding through the two pilings, I came about, much to the chagrin of my brother and wife. I was not ready to wreck my new boat on the rocks the first time out. We headed back the way we came, and headed towards the south side of the rock jetty by Coronado. We emerged into what was finally obviously the Navy's beach front shoreline on Coronado. Admitting my error, we turned around again and entered the bay channel for the second time. This time we followed the channel lights all the way to the Coronado Bridge. Each passing moment brought more dew and more cold. We were shivering in the night, and our hands were in pain from the wet cold in our fingers. Debbie was tucked away in a sleeping bag below, while my brother and I remained on deck. We were warned by employees at the marina not to attempt entering the south bay channel at night. They warned us that if one strayed out of the channel, one would surely run aground. We followed the channel lights all through the early morning hours in the glow of the city on the bay. The channel was clearly marked, so we again elected to make for the marina in the dark. Half frozen now and dead tired, we traveled south along the row of Navy ships moored in the naval yard. The channel was easy to follow. We passed the Navy ships slowly. Finally, according to our chart, we were at the entrance to the channel leading into the south bay and the marina. Ever so carefully, we watched the green lights and the red lights, taking care to motor directly down the middle of the channel. So far, so good. According to our chart, the water all around us was extremely shallow. Notwithstanding the shallow depth, the lights directed us into the night. We simply obeyed what we saw. We aimed directly between the green and red lights. Suddenly, the boat nose-dived forwarded and came to an immediate stop! We were aground, frozen, and tired. We kicked the Nissan into reverse and gunned the engine. We backed out of the shallow water, very happy not be be aground. The boat appeared to be in good shape. No visible damage anyway. We tried again, thinking maybe we were not dead center in the channel. We came in slowly this time. The front of the boat nose-dived a second time. Again the motor pulled us back out of the mud. We did it a third time. Same result. Once again, the motor saved us. TO BE CONTINUED |

|

|